Today the EU Commission reminded us on a study conducted by Deloitte Luxembourg on Distribution system of retail investment products across the EU published in April 2018. The study investigated how well EU retail investment markets work for consumers, covering 15 Member States. Unsurprisingly, the study concluded that although consumers have choice, they face significant challenges in collecting and processing information for making good investment choices (see the summary of findings here and the full study here).

Thursday, 28 June 2018

Wednesday, 27 June 2018

C-191/17 AG Tanchev on the notion of 'payment account'

Last week Advocate General Tanchev delivered a not very

‘consumer friendly’ opinion

in case C-191/17 Budeskammer fur Arbeiter und Angestellt v ING-DiBa

Direktbank Austria Nidererlassung der ING-DiBA AG. Referred by the Oberster

Gerichtshof (Supreme Court of Austria) this case involves the the

interpretation of Article 4 (14) of Directive 2007/64/EC on payment services in

the internal market (PSD 1).

Representing consumer interests the Budeskammer fur

Arbeiter und Angestellt brought an action against ING-DiBa Direktbank Austria

alleging that the bank’s ‘Direkt-Sparen’ (‘direkt-savings’) product

(referred to as online direct savings

account) contains a large number of standard terms and conditions that are

not compliant with the Austrian law transposing PSD1. Given the special nature

of the financial product, the subject of the dispute became the scope of PSD1,

i.e. whether this particular kind of account qualifies for a payment account

within the meaning of PSD1.

Article 4 (14) PDS1 provides that a 'payment account' is an account held in the name of one or more payment service users which is used for the execution of payment transactions. The definition itself neither specially refers to nor specially excludes the particular product in question.

What is an online direkt savings account and how it works?

The online direct savings account is a particular kind of bank account. It is labelled as a savings account, i.e. that should be used for depositing money for saving purposes. however, access to this account is granted via online banking, enabling consumers to make deposits and withdrawals from the account. Any transfer however must be carried out through another account called a reference account. The reference account must be a current account opened in Austria, but can be held by any Austrian bank, it does not have to be held with the same bank that holds the online direst savings account. A consumer is able to decide, without any restriction or notice when and in what amount the consumer transfers money between the online direct savings account and the reference account.

Is the online savings account covered by PSD1?

Interpreting the provision in question in the context of other provisions of PSD1 (other definitions within Art. 4, Art. 2, and the Annex) and related EU legislation (Directive 2014/92/EU and Regulation 260/2012) AG Tanchev concluded that the particular product cannot be considered to be a payment account within the meaning of Article 4 (14) of PDS1, because this account does not involve ‘direct participation in payment transactions with third parties’.

Our evaluation

Although AG Tanchev rightly said that the mere labeling of an account as a ‘savings account’ is not in itself an indication that the account does not constitutes a ‘payment account’ within the meaning of PSD1, what seems to have been determinative in his reasoning was that the online direct savings account is not intended to be used for transactions between the consumer (account holder) and third parties, essentially accepting the argument of the defendant bank. Whilst this may be true, if the account allows for consumers to execute payment services consumers would surely deserve to have the same level of protection that belongs to users to payment accounts. According to AG Tanchev, this protection will be provided for consumers via the protection they enjoy buy the underlying, reference account. Whilst this may be correct, by the same token, applying a different regime for the two accounts creates uncertainty and opens a potential protection gap for consumers. In case of a future dispute, the bank holding the online direct savings account would be able to use the same argument as a shield against their liability; that the higher level of protection offered by PSD1 attached to the reference account does not apply the transaction executed though the online savings account, because the transaction was attached to that separate account and not to the reference account. The situation gets even more complicated leaving consumers with less access to redress when the two accounts are held by different banks.

At this instance we must agree with the EU Commission’s

submission that argued against the restrictive approach in interpreting the

scope of PSD1. The EU Commission stressed that the purpose of PDS1 is to confer

protection on the users of payment services: as mentioned in recital 46

and in the articles of Title IV of PSD1. The accounts covered by PSD1

benefit from certain minimum regulatory requirements for the proper execution

and processing of payment transactions, and such protection is denied to

consumers in the event of a restrictive interpretation of the notion of a

‘payment account’ within the meaning of PSD1 (para 21).

Whilst the opinion involves the interpretation of PSD1, it remains relevant in the light of the current PSD2 that contains exactly the same provision in Article 4 (12) and seems to makes no special reference to the features of the product under scrutiny here.

Monday, 25 June 2018

BEUC position paper on artificial intelligence

Last week BEUC published a very interesting paper on Automated decision making and artificial intelligence: a consumer perspective. The paper highlights the main challenges raised by AI and suggest ways to tackle these. Importantly, the paper calls for an EU Action plan on AI that would set out new consumer protection concepts and a comprehensive plan to update the old consumer protection tools. The position paper is a must read for everyone interested in the impact of new technologies on consumer protection.

Representative actions in the Visegrád 4 countries – real improvement? by Rita Simon

This is a guest post by dr Rita Simon from the Institute of State and Law at the Czech Academy of Sciences that has been based on a report prepared by her for BEUC

Representative actions in the Visegrád

4 countries – real improvement?

Mass harms cause a mass of problems. In mass harm situations, collective claims

constitute a better means of access to justice than individual ones, especially

regarding bagatelle harms. Although certain collective redress mechanisms exist

all over Europe, their effectiveness is questionable. Studies such as “Evaluation

of the effectiveness and efficiency of collective redress mechanisms in the

European Union” and the “Fitness check of consumer law” showed that the existing

redresses are rarely used or they do not produce the desired results, in almost

all Member States. We can also observe the ineffectiveness of injunction

actions in the V4 countries. The New Deal for Consumers, which has been

published in April this year, aims to

strengthen the enforcement of consumer rights, which is the Alfa and Omega of

consumer protection. The proposed way of improving enforcement by the European

Commission follows the German, Austrian and French practice: the launch of representative

actions by consumer organisations will be supported more strongly by the

Commission. However, the question of whether such actions could be the best

solution for enforcing consumer rights and access to justice in the V4

countries should be posed.

Injunctive reliefs

Depending on who has the right to file for an injunction and how effective

the action is in practice, some key differences should be observed. In the Czech

Republic, only consumer protection organisations can file for injunctive relief;

in the other three countries some control authorities, such as the financial surveillance

authority or office of consumer protection or consumer ombudsman can also initiate

injunction actions. How often these authorities file an action often depends on

the consumer policy of the government in power. An interesting fact is that in

Hungary – similarly to in Spain - the state advocate also has the right to file

an injunctive action if the public interest is affected. Such actio popularis actions have been very effective

in eliminating unfair clauses, e.g. in financial service contracts. The yearly total

of filed injunctive actions is very low in the Visegrád 4 countries, at not

more than 1-2 actions per country. However, it should be pointed out that in

Hungary and Poland compensatory collective redress is available in combination with

an injunctive action, which significantly increases the impact of such a redress.

In contrast with this, in the Czech Republic, the consumer organisation often withdraws

the filed action, because of the length of the procedure or due to competency

problems between the courts and other supervisory bodies. In Poland, the

President of the Competition and Consumer Protection Office (UOKiK) does not have an obligation to initiate an

injunction procedure automatically at the request of a consumer organisation or

the ombudsman; it is at his discretion. A further criticism is that an

injunction decision against a foreign trader is not enforceable, and it is

reported in all the Visegrád countries that consumer organisations generally

lack sufficient financial and human resources. The impossibility of consumer organisations

to demand monetary compensation is problematic in the Czech Republic and

Slovakia.

Other existing mechanisms – class action, and actio popularis

Class action mechanisms as a form of group action have been in force

since 2010 in Poland, and in Hungary since January 2018. Group actions popped

up in Poland like mushrooms and were filed in very different areas, such as

construction disasters, mass poisoning and unfair clauses in credit or travel

contracts, but also against motorway operators and against a regional

authority. The number of suits initiated is over 100, but many claims were rejected

due to the limited scope of application of the class action. Class actions can

be initiated exclusively regarding tortious conduct and product liability, but

claims for personal injury and infringement of human rights (health, body integrity, good reputation image, etc.) are excluded from the

scope. In contrast, the Hungarian scope of application does not exclude

personal injury, but limits the fields of law in which class action can be

used. Therefore, a group action can be filed in Hungary in labour and consumer

disputes and over some health claims resulting from environmental damage. Group actions

in both countries follow in some respects the US class-action model but, regarding

joining the group, just an opt-in possibility is given, and the Polish model in

particular contains numerous safeguards to avoid malicious, ruinous claims.

As other interesting collective redress, Hungary improved its “actio popularis” rules in 2012 and

differentiated between so-called public

interest actions and public interest

enforcements, which can be commenced if the infringement has harmed a large,

identifiable group of consumers, or has caused a significant disadvantage. The

public interest action can end in two ways, first with a declaratory judgment establishing

the infringement or second with a cease and desist order on its own or with a

case order accompanied by a restitution order. In the first model, which ends

with the declaratory judgement, consumers have to file a simplified follow-on

damages claim. In this claim, they need to prove the causal link between the

infringement and the extent of the damage suffered. A public interest enforcement presumes a prior administrative process

that has established the infringement. Despite high expectations, this type of

claim has so far not achieved its purpose. Collective actions have been filed much

less often after the amendments than before 2013. This can be explained by the

continuing decline in consumer financing and the abolition of the Department of

Collective Action at the Consumer Protection Agency. In addition, the

reluctance of consumers to file follow-on complaints regarding the damage suffered

needs to be emphasised, as does the lack of information on the existence of actio popularis decisions.

Unlike in Hungary and Poland, the two other Visegrád countries have not

introduced new group action mechanisms yet; the Czech legislator is working on

a class-action proposal, but the new government has not given

priority to this entering into law. Business associations, especially the

banking association, have been trying to have the legislation shelved until the

new Directive on representative actions has been announced.

Are representative actions suitable collective redress models for the V4

countries?

The proposal for the Directive allows "qualified entities",

such as consumer organisations (but also ad hoc entities), to launch actions on

behalf of all consumers. These entities will have to satisfy minimum

reputational criteria (they must be properly established, not for profit and

have a legitimate interest in ensuring compliance with the relevant EU law).

Compensatory collective redress actions will also be available. A very

important feature of these actions is that, in order to protect the interests

of consumers, the above-mentioned entities will be entitled to seek redress by

repairs, exchanges, reductions and termination of the contract or repayment of

the purchase price. A very interesting innovation is that if a prior

administrative or court decision has assessed an infringement, it should be

taken as irrefutable evidence in any subsequent redress action not just in the

same but also in other Member States. This emphasis on the acceptance of court

and administrative decisions should avoid legal uncertainty and unnecessary

costs for all parties, including the judiciary. Such a new development could certainly

bring positive changes; the only question to pose is whether the legitimacy of

bringing representative actions should be reserved for consumer associations

alone.

In the Visegrád 4 countries, there is considerable concern that - due to

the lack of funding of consumer organisations and the impossibility of

receiving funding from third parties - these entities will not be able to

perform properly. The situation, which has been observed in current injunction

practices, will not improve in the future. It should therefore be recommended

that other state organisations (e.g. consumer authorities, the ombudsman,

financial supervisory authorities and trading standards agencies) should also receive

the right to launch these collective actions. The state organisation has better

access to evidence and it has a bigger legal department than consumer organisations.

To support the participation of consumers in civil law proceedings, it seems useful

to introduce parallel “clean” opt-in class action models in all the Visegrád

states. It is also recommended to define the form and content of simplified

individual follow-on-damage claims, similar to the Hungarian model after public interest/enforcement actions. These

changes should be proposed with sufficient precision at the European level,

because otherwise is can be assumed that the national legislatures of some

countries (including the Visegrád states) would not make their collective redress mechanisms significantly

more effective, due to the resistance of business and banking associations. Without

simple, clear and feasible collective redress, the enforceability of consumer

rights will not improve in Slovakia and the Czech Republic at all and just a

new rule on paper will be announced.

Wednesday, 20 June 2018

Workshop 'Vulnerable consumers or citizens?'

Christine Riefa (Brunel University) and Severine Saintier (University of Exeter) are organising a workshop Global Consumer Lives: '(Vulnerable) consumers or citizens?: is there a correct rationale for a fairer access to justice' on July 10 at Brunel University. Find more information at this website.

Friday, 15 June 2018

AG opinion in Wind Tre: aggressive practices require active conduct

On the 31st of May the

AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona's opinion in the Wind Tre cases (C‑54/17 and C‑55/17) was published. This is the first case where the meaning of

aggressive commercial practices is discussed, making it highly important.

Before Wind Tre the only ECJ case on aggressive practice was Purely Creative (C-428/11), in which one of the blacklisted practices was contested, without invoking art. 8-9 of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD, Directive 2005/29/EC).

On the 31st of May the

AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona's opinion in the Wind Tre cases (C‑54/17 and C‑55/17) was published. This is the first case where the meaning of

aggressive commercial practices is discussed, making it highly important.

Before Wind Tre the only ECJ case on aggressive practice was Purely Creative (C-428/11), in which one of the blacklisted practices was contested, without invoking art. 8-9 of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD, Directive 2005/29/EC). In the Wind Tre case the issue of the relationship between sectoral legislation, such as the Universal Service Directive (Directive 2002/22/EC), as lex specialis to the UCPD and the general rules of the UCPD is discussed.

Facts of the case

The dispute concerned the marketing of mobile phones in Italy. The mobile

phones came with SIM cards which had answering and internet services

pre-installed, of which fact consumers had not been informed. It is important to

note that there was no complaint as to the cost of these services or the

information provided about their function, the complaint was about telecom

companies omitting to inform consumers that these services were pre-installed.

The same practice was used by two companies, Wind Tre and Vodafone Italia,

and the Italian Market Authority (Autorità Garante della Concorrenza e del

Mercato, hereafter AGCM) imposed fines on the two companies for engaging in an

aggressive practice. The telecom companies challenged that decision in court,

claiming that the AGCM lacked competency to impose fines stating that the

telecommunications authority (Autorità per la Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni,

hereafter: AGCom) was responsible instead. This argument was based on art. 3(4)

UCPD stating that in case of a conflict between the UCPD and other sectoral rules

on unfair commercial practices, the latter will prevail and apply.

The case reached all the way to the Council of State (Consiglio di Stato)

which ruled in favour of the competence of the AGCM stating that the practice

was aggressive within the meaning of the Italian Consumer Code (transposing the

UCPD). It argued that even though sectoral legislation of the

telecommunications sector was also breached, the case in question presented a

‘progressive harmful conduct’, which gave rise to a more serious infringement,

thus making the application of the Consumer code, instead of the sectoral

legislation, appropriate. (para 25)

Questions

The Italian court referred 7 questions, which the AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona, with the agreement

of all parties, summed up into the following two groups (para 32).

- Can the conduct of the telephone operators be classified as an ‘unsolicited supply' (as per point 29 of Annex I of the UCPD) or an aggressive commercial practice?

- According to art. 3(4) UCPD should the UCPD cede to other EU rules, and, if so, to national provisions enacted in implementation of those rules?

The first group of questions refers is of a substantive nature as to

whether the practice in question can be characterised as aggressive according

to the UCPD; either using the blacklist of the UCPD, or by using art. 8-9 UCPD.

The second group of questions refers to the relationship between the UCPD

and other EU sectoral legislation as lex specialis.

AG's Opinion

In answering the first question, AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona provides us with what has been

the most detailed analysis of the elements of aggressive commercial practices

by the Court to this day.

Inertia Selling

He begins to first examine whether the practice in question can be caught

by the blacklist, and specifically point 29 forbidding inertia selling.

According to the AG, there are two conditions to satisfy simultaneously: 1) unsolicited supply

and 2) unlawful demand of payment (para 44).

From the facts it can be established that the phone operator had not

properly informed consumers on the pre-installed services on the sim card,

meaning that consumers could use them without configuring them. AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona examines

whether this supply, of which consumers were not informed of, qualifies as

‘unsolicited supply’. In his opinion ‘unsolicited’ means more than not being

provided with essential information on a service, it means that the consumer

was not aware of its existence (para 48).

The AG finds that a consumer (and not the average consumer) has no reason

to expect that services have been preinstalled, if he has not been

informed thereof and which he has to opt out of by using a process which he is likely to

be unaware of (para 53).

Hence, whilst in this case unsolicited supply is possible, the AG does not find the same

for the demand for payment. In his opinion not any demand for payment could fulfil the

conditions of point 29, but it needs to be an undue request for payment. The

referring court specifies that there was no complaint as to the cost of the

services or the information about them, only about the lack of information about the pre-installation.

AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona argues further that the average consumer could expect that the SIM card

purchased would be able to provide him with services about the costs of which

he has been informed.

It is worth noting that the AG makes reference to the average consumer in the context of the blacklist, where the average consumer test is not meant to apply. This goes to show that the blacklist does not offer the legal certainty promised.

It is worth noting that the AG makes reference to the average consumer in the context of the blacklist, where the average consumer test is not meant to apply. This goes to show that the blacklist does not offer the legal certainty promised.

Based on the above reasoning, point 29 of Annex I of the UCPD on inertia selling is not

applicable. The next step is to examine whether the practice can be caught by

art. 8-9 UCPD.

Aggressive Practices

The focus is on the practice in question being one of omission of information.

AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona looks to the factors of art. 9 UCPD to determine what would qualify as a

practice using the notions of: harassment, coercion or undue influence. Out of art. 9 UCPD the

AG deduces that harassment and coercion cannot be applied in this case as they

require ‘active conduct, which is not

present in the case of an omission of information’ (para 64).

It is not clear how the AG reaches that conclusion, as the factors of

art. 9 UCPD apply for all three categories of harassment, coercion and undue

influence without distinction. Also, even the omission of information requires an

active choice of the trader to omit that information, so one could argue that

active conduct is not entirely absent.

The AG continues to examine solely whether the practice can be caught

under the concept of undue influence. Undue influence is the only one defined in UCPD in its art.

2(j), unlike harassment and coercion.

Undue influence refers to exploitation of a position of power which

significantly limits the ability of the consumer to make an informed decision.

The AG differentiates between two different kinds of positions of power (para

67):

- Exploitation of a position of power which allows the trader to infringe the consumer’s freedom when it comes to buying a product.

- Position of power held by a trader who, following the conclusion of the contract, may claim from the consumer the consideration which the latter undertook to provide on signing the contract.

Consequently, the AG defines a position of power in undue influence as both applying in pre-sale and

post-sale conditions. What is to be noted is the focus on the fact of the conclusion of a contract,

of consideration of the terms, that is the use of contract law terms through which aggressive practices seem to be defined. However, aggressive practices are broader than that, to

the extent that they cover all transactional decisions of the consumer and are

not limited to the decisions to enter into a contract.

The opinion explains that the aim of prohibiting aggressive practises is,

in essence, protecting the freedom of contract, as consumers should be bound only

by obligations that they freely entered into. So the criterion is whether

the omission of information about the pre-installation impaired the freedom of choice

of the consumer to the extent, where he accepted contractual obligations he

would not have otherwise (para70).

AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona found the practice not to be aggressive, as according to him, the

practice was not sufficient to impair the freedom of the consumer to such an

extent that he would not have entered the contract. The AG does not elaborate

on how he reached that conclusion or what is the standard against which it is

weighed. This view of aggressive practices appears to raise the standard,

making it more difficult to show that impairment of the freedom of choice of

the consumer is indeed significant enough.

Lex specialis

Given the answer to the first two questions, there was no reason to

examine the rest, on the conflict of law, yet the AG did submit his observations.

In these he makes the accurate observation that the UCPD is not designed

to fill the gaps that sectoral legislation leaves; instead it offers its own

stand-alone system of protection which exists in parallel with the sectoral

legislation (para 94). This sets the tone also for art. 3(4) UCPD that should be

interpreted strictly as focus should be on maintaining a high level of

protection. Therefore, art. 3(4) UCPD is better conceptualised as regulating

conflict between provisions and not systems of sectoral legislation (para 111).

In this case, it means that the existence of sectoral legislation that covers

aspects of unfair commercial practices does not preclude the application of the UCPD.

AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona didn’t find a conflict in this case between the UCPD and the

Universal Service Directive, but rather the need for them to be applied

jointly (para 129). The Universal Service Directive regulates the information

requirements, which are crucial for determining whether there was unsolicited

supply as per point 29 of the Annex I of the UCPD.

Conclusion

This is an intriguing case, as it

is the first of its kind for aggressive practices in the UCPD. It reveals

contrasting interpretation of the UCPD notions and objectives between the Member States and AG Campos Sánchez-Bordona. Italian authorities

viewed aggressive practices as a tool for penalising the abuse of power by the

trader. The AG on the other hand interpreted the same provisions focusing on

protecting consumers' contractual freedom, especially as applied to the decision to enter into a contract.

It remains to be seen what the Court will decide and this blog will follow the

developments with great anticipation.

Thursday, 14 June 2018

"Food labels: tricks of the trade" - BEUC's report

On the same day that the Commission announces common methodology on comparing quality of similarly packaged food products, BEUC publishes its report "Food labels: tricks of the trade" on misleading labeling practices in the food sector in the EU (see more Food labels can fool you...). Three practices that have been further elaborated on are:

- labeling products as 'traditional' or 'artisanal';

- displaying fruit pictures on packaging for products that have little or no actual fruit content;

- labeling as 'whole grain' products with barely any fibre.

BEUC calls for:

- more definitions on the EU level of commonly used terms on food products' labels, such as 'natural', 'traditional' or 'artisanal';

- setting a minimum level of whole grain content for 'whole grain' claims;

- setting a minimum level of content for ingredients pictured on the front of the pack, e.g. fruits;

- obliging traders to display on the front of the pack the percentage of the advertised ingredient.

|

| E.g. the report mentions that while this product has many fruits on the packaging, they are only 2.5% of all ingredients |

Quality matters

Today the Commission has published a new common methodology that will allow national authorities to compare the quality of food products across the EU, when they compare the composition and characteristics of these food products (Dual quality of food...). The idea behind this project being that currently similarly branded or packaged food products may differ in composition to an extent that is misleading to consumers, but the comparison between these products as well as the finding of misleading action would differ per Member State, leading to different levels of consumer protection. This common methodology emerged from the activities of the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission's Science and Knowledge service, which facilitate evaluation of differences in the quality of food products in an objective way.

Today the Commission has published a new common methodology that will allow national authorities to compare the quality of food products across the EU, when they compare the composition and characteristics of these food products (Dual quality of food...). The idea behind this project being that currently similarly branded or packaged food products may differ in composition to an extent that is misleading to consumers, but the comparison between these products as well as the finding of misleading action would differ per Member State, leading to different levels of consumer protection. This common methodology emerged from the activities of the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission's Science and Knowledge service, which facilitate evaluation of differences in the quality of food products in an objective way. Sweep of telecommunication and other digital services websites

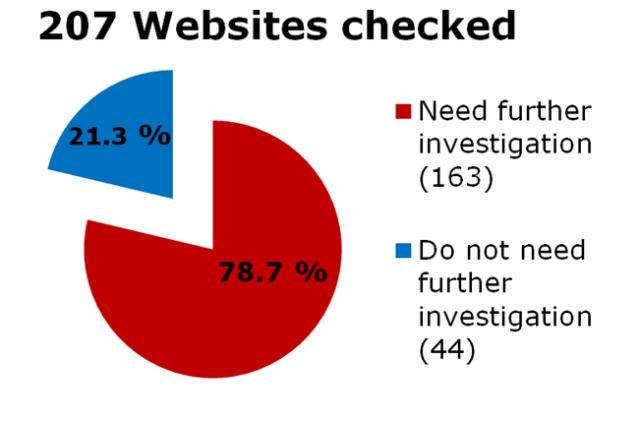

On May 18 the European Commission and national consumer protection authorities published their new sweep report revealing misleading commercial practices adopted by websites offering telecommunication (e.g. fixed/mobile phone, internet) and other digital services (e.g. streaming) (see more Buying telecom services online...). Out of 207 screened websites - 163 could be currently infringing EU consumer law. The most common suspicious practices concerned:

- incorrectly advertising certain packages as free or discounted, as in fact these belonged to a bundled offer;

- not offering a dispute resolution system (or link to ODR);

- maintaining a possibility of unilateral change of T&Cs without adhering to rules on notification or providing a justification;

- providing incorrect or misleading information on refunds in case of either withdrawal from the contract or non-conformity;

- automatic contract renewals without properly informing consumers about this.

|

| From the EU Commission website |

Thursday, 7 June 2018

Connecting fights saga tbc - AG Tanchev in flightright (C-186/17)

Last week we have discussed the judgement of the CJEU in the case Wegener (C-537/17), in which the CJEU confirmed that it doesn't matter whether a delay upon the arrival at the final destination was caused by a delay of one of the connecting flights, as long as they were part of one booking, the passenger could claim compensation from art. 7 Regulation 261/2004. Yesterday, AG Tanchev had to address this issue again in an opinion to the case flightright (C-186/17).

The difference between the factual situation of these two cases was that the contractual air carrier differed from the operating air carriers. In this case, passenger booked his flights through a tour organiser, who had a contract with Air Berlin. The latter air carrier has, however, on the basis of code sharing agreements, allowed the contract to be performed by Iberia Express, Iberia and Avianca - three air carriers for three flights of the whole, connected journey from Berlin via Madrid (first flight) and via San Jose (Costa Rica) (second flight) to San Salvador (El Salvador) (third flight). The first flight, operated by Iberia Express, was delayed - only by about an hour, but this led to a missed connection and arrival in El Salvador with 49-hour delay.

Surprisingly, the German court dismissed the claim against Iberia Express, claiming that they weren't the operating air carrier on all flights and that they were not involved in the planning and booking of the journey, and, therefore, could not have taken the operational risk of short connection times. This would have been an acceptable reasoning except that provisions of the Regulation 261/2004 are crystal clear in assigning the obligations towards passengers (incl. compensatory ones) to operating carriers - regardless whether they have had contractual relationships with the passenger and, therefore, whether they have planned the flights. On the basis of code sharing agreements, the operating carrier could possibly try to claim redress from other involved parties (on the basis of Art. 13 Reg 261/2004). Such division of liability facilitates high level of consumer protection - as it is easiest for passengers to turn towards the operating carrier with their claims - as well as prevents possible manipulation of flights by air carriers, trying to evade liability by splitting up flights (see para 41 of the opinion, as well).

AG Tanchev rightly then advises the CJEU to recognise the need to hold the operating air carrier liable.

Sunday, 3 June 2018

Is Big Data harmful to our financial well-being?

On the 15 of March a Joint Committee of the European Supervisory Authorities - ESAs (consisting of the European Banking Authority-EBA, the European Securities and Markets Authority- ESMA and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority-EIOPA) published their final report on the impact of Big Data on our financial well-being. The overall conclusion of the report is that the potential benefits outweigh the risks posed by Big Data.

Big Data is a flow of data from our daily online activities that is collected and processed with highly sophisticated IT tools. This may include information from our social media presence, internet browsing history, smart phone signals or data generated by using a payment card. Connecting information from various sources enables financial firms to offer tailored financial products and services to us, their customers.

Financial firms are increasingly reliant on Big Data. This this is like to increase in the future with the fast developing Fintech sector that developed exactly with the aim to compete with traditional firms by providing better suited products to consumers. Fintech is likely to develop faster in the future due to regulatory initiatives such as Open Banking in the UK (see our report here) that mandates banks to share their customer information with Fintech firms upon the consumer's request.

The advantages of Big Data are undeniable. First and foremost, Big Data enables firms to personalized financial products to meet the needs of their customers. Big Data opened the door for innovative, tailored financial products that would not be previously available from mainstream financial providers. This is largely because Big Data enables financial firms to connect non-financial information derived e.g. from our Facebook activity with financial information about our savings to create a better picture about our savings and investment habits, and than to tailor their offer in line with our habits. Secondly, Big Data also enables firms to design their provision of information in a way that can be useful to consumers. For example, the insurance company is able to provide the consumers with a warning that the insurance policy does not cover a parachute jump, which the person recently announced on social media. Finally, the use of Big Data can result in cheaper products for consumers. For example, inexperienced drivers could benefit from lower insurance premiums if they are able to prove that they are driving responsibly. This can be done by installing a telematics device in their cars that will enable insurance companies to check and analyse their driving habits.

The use of Big Data also carries risks. The primary risk is that Big Data is misinterpreted. For example, movements of a doctor that works night shifts could be interpreted as a indication of an unhealthy lifestyle, and as a result a consumer may be denied access to financial services for example a loan. Secondly, consumers may be overloaded with information about various, highly specific products that are difficult to compare and they may end up with a product that is not the best match to their needs. Thirdly, consumers may be also overwhelmed with targeted offers and may end up buying a product that they do not really need. Finally, as every data, Big Data is also vulnerable to cyber attacks.

Given the risks and benefits, the impact of Big Data on our financial well-being is largely dependent on us, on our digital footprint. Firstly on what sort of digital medium we are present, and secondly, what conscious steps we take in making decisions on the information we share. The ESAs warn us that firms are obliged to inform us on what sort of data they collect about us and how they store it, and that we need to make sure that we understand how our data may be used. However, the recent application of the new GDPR (see our report here) and the many privacy notices we received in recent days reminded us on just how many spaces we are present, and just how many companies store our personal information, many of which we do not even remember signing up for. We were also asked to review our privacy settings, seemingly placing us in driving seat in deciding on the information we are willing to share. But how can we decide on ticking one box rather than the other without knowing the full implications of our decision? For example, a doctor doing frequent night shift may never find out that his/her loan was refused because of misinterpreted information, even is he/she does, he/she might be unaware on just how many occasions he/she agreed to share his/her location, and where he/she needs to go now to turn these settings off. Is control over our Big Data illusionary? Will Big Date be harmful to our financial well-being without this control? What do you think?

Saturday, 2 June 2018

When does an online seller become "a trader"? AG Szpunar in Kamenova

Last Thursday the Advocate-General Szpunar delivered an opinion in case C-105/17 Kamenova, in which the Court of Justice was asked to provide interpretation of Article 2(b) and (d) of Directive 2005/29/WE on unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices (UCPD) in the context of a sale of goods via an online platform. The provisions included in the preliminary reference contain definitions of the very basic concepts used throughout the UCPD and in the European consumer law more generally. The broader relevance of the guidance to be provided has been recognised by the Advocate-General who decided to extend the the scope of the questions referred to also cover a provision of Directive 2011/83/EU on consumer rights (CRD).

The request for a preliminary ruling was submitted by a Bulgarian court adjudicating a dispute between Ms. Kamenova and the national consumer protection authority concerning a potential breach of consumer law by the former. More specifically, Ms. Kamenova, who had been engaged in the sale of goods via an online platform, and had published eight different listings at the same time, did not provide information required by the Bulgarian act on consumer rights, which implemented Directive 2011/83/EU into national law. The defendant argued that, when offering used goods via olx.bg, she was not acting in a professional capacity and, consequently, her activities remained outside the scope of that act. The consumer protection authority held an opposite view and insisted that, by acting in breach of the act on consumer rights, Kamenova engaged in an unfair business-to-consumer commercial practice.

"Trader" in the UCPD and in CRD: a uniform interpretation?

Before addressing the crux of the case, AG Szpunar considered it necessary to establish whether the notion of a trader used for purposes of Directives 2005/29/WE and 2011/83/EU is to be construed in the same way. Indeed, as observed in the opinion, the wording of respective provisions is almost identical. The AG did not stop here, however, but observed that further factors had to be considered. These included, in particular, the level of harmonisation provided by respective Directives, which, in turn, should be assessed by reference to the wording, meaning and purpose of the interpreted acts. The AG eventually responded in the affirmative, finding that both Directives aimed to fulfil the same objectives, namely to contribute to the functioning of the internal market and to ensure a high level of consumer prtoection, and that both of them established a full level of harmonisation. To ensure coherent application of the two sets of rules, according to the AG, the notion of the trader used in the UCPD and the CRD had to be interpreted uniformly.

The threshold for becoming a "trader"

The subsequent part of the opinion concerns the substantive interpretation of the trader's notion as provided in the two legal acts. In this respect, Article 2(b) of the UCPD (and similarly Article 2(2) of the CRD) defines the notion of a trader as "any natural or legal person who, in commercial practices covered by this Directive, is acting for purposes relating to his trade, business, craft or profession and anyone acting in the name of or on behalf of a trader". The opinion of the AG provides for some useful points of reference in that regard. Most notably, it does not only list the criteria to be considered in the analysis of one's activity, but also points to the deeper normative rationale of the analysed provisions - namely the weaker position of the consumer resulting in the trader's comparative advantage.

As discussed in paragraph 51 of the opinion, assessment of the purpose of the seller's activity should depend, among others, on questions whether:

- the sale was made as part of an organised activity and with a profit-seeking motive;

- the sale was subject to a specific timeline and frequency;

- the seller had a legal status which allowed him to conduct trading activity and to what extent online sale was linked to such activity;

- the seller was a VAT taxpayer;

- the seller was acting in the name or on behalf of another trader or through any other person acting in his name or on his behalf and obtained remuneration or a share in profit in this connection;

- the seller had purchased new or used goods for pursposes of their resale, as a result of which his activity became organised, frequent or concurrent to his professional activity;

- the level of profit generated from the sale confirms that the transaction belonged to the seller's trading activity;

- all products offered for sale by the trader were of the same type and value, in particular, whether the offer concerned a limited number of products.

In formulating the aforementioned list the AG relied, among others, on the submissions of the German government and of the European Commission. The involvement of these two actors in the proceedings is not surprising - German courts have been called upon multiple times to decide on similar cases and the Commission tried to come up with a similar list in its 2016 communication on collaborative economy. According to the AG, the criteria mentioned above are neither exhaustive, nor exclusive, meaning that fulfilling one or more of them does not, in itself, determine whether a seller should be qualified as a trader. The relevant assessment should be made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the normative rationale mentioned above. With respect to the analysed case, the AG expressed scepticism whether publication of eight listings on an online platform could be qualified as an activity of the "trader" and, consequently, a "business-to-consumer commercial practice". Which factors the AG found decisive for reaching this conclusion is not clear, which may be a point of criticism addressed at her otherwise helpful guidance. Another possible takeaway from the analysed case is that national legislators may want to think twice before establishing strict thresholds between professional and non-professional activity. As for now, it remains to be seen whether the Court of Justice will follow the opinion of its advisor and how specific the Court's judgment will be. Most likely, a case-by-case assessment - first undertaken by the sellers themselves and then verified by the courts, enjoying a wide marging of appreciation - will remain the norm for the future. This would be a rather conventional way of striking the balance between certainty and flexibility with no special treatment being granted to the digital economy. Such an assessment is also substantiated by the amendments to the CRD proposed recently by the Commission, which generally leave the allocation of responsibility for establishing the status of the contracting parties unaffected. As mentioned in our previous post (see: New Deal for Consumers...), new provisions would impose an obligation on online marketplaces to provide information whether the third party offering the goods, services or digital content is a trader or not, on the basis of the declaration of that third party. Bolder measures proposed in the literature, aimed at levaraging the potential of data collected by the operators of online platforms, as for now remain off the table.